Na Mira: “Passages Paysages Passengers”

This Video Viewing Room features an experimental video by Na Mira, Tesseract (test) (2020), with related archival images from a 1982 screening of a work by Theresa Hak Kyung Cha that took place in The Kitchen’s Video Viewing Room. It is accompanied by an introductory text by 2020–2021 Curatorial Fellow Kathy Cho and a narrative written by Mira on the process of creating Tesseract. Altogether this Video Viewing Room is a presentation of collective, in-progress research on Cha. Mira’s video was available to view from May 26–June 25, 2021.

This presentation is organized by Kathy Cho, 2020–2021 Curatorial Fellow.

I took the course “Modern Poet: The Imagist Poem” during my first semester of undergrad, where I was introduced to Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictée (1982), taught amongst writing by a fairly diverse list of poets. Since this initial encounter, I have eagerly consumed anything else that gets produced around or unearthed on Cha. Sometimes I actively search for her, other times she finds me.

The Kitchen’s Video Viewing Room was a dedicated space for film and video screenings within The Kitchen’s buildings from 1975 through the early 1990s. While looking into the archives of Video Viewing Room programs, I came upon traces of Cha’s screening of Passages Paysages (1978). After a maze of digital searches, I learned more details of how her video was shown as part of Women’s Work: A National Collection of Video by Women guest curated by Ann-Sargent Wooster. This survey of twenty-six video works screened from 4–5PM daily on February 2–27, 1982.

Women’s Work was one of sixteen independently curated exhibitions sponsored by the Women’s Caucus for Art under the overarching title Views by Women Artists. The exhibitions took place simultaneously in spaces all over the city, including commercial, non-profit, and university galleries, as well as government buildings. The artists were chosen from an open call and categorized by medium and/or themes. There were almost 400 women included across the sixteen exhibitions, and it’s noted that almost double the number applied to the open call. Like most survey exhibitions, Views by Women Artists feels simultaneously monumental and anonymizing.

In tandem with the month-long Video Viewing Room presentation, Wooster organized an additional evening screening of selections from Women’s Work on February 14, 1982. The brief language on The Kitchen’s press release states that the Valentine’s Day screening will emphasize work not previously shown in New York, including two multi-channel pieces—Mary Lucier’s Denman’s Col (Geometry) and Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Passages/Paysages. I tracked down and got shipped a copy of the exhibition catalog, where Wooster writes:

5. Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, New York City. Passages/Paysages, black and white, three channels, 10min., 1978: This three channel piece is a haunting combination of visual and aural poetry. Images and words, seen in French but heard in English (Allumer: to dim), deal with the elusiveness of memory and the sense of loss experienced when we attempt to capture it. Using three monitors extends the piece, like the action of memory, horizontally and vertically in time, allowing her to build a contrapuntal pattern of voices like a round.

***

Considering what has already been written and exhibited around Cha’s legacy, for this Video Viewing Room, I wanted to focus on the gaps within her history, where we often meet. My research within The Kitchen’s archives is further informed by ongoing negotiations on representation, legibility, and who is made visible within various archives. How do these gaps leave space for writers and arts practitioners to utilize projection, speculation, and channeling to expand upon a seemingly fixed point?

I previously worked with Na Mira to present her video A Woman is not a Woman (2014–2015), which I later learned included text from Dictée. There are recognizable overlaps in Mira and Cha’s practices, including but not limited to the relationship between experimental writing and video, and an in-depth matrilineal connection to Korean shamanism. With this in mind, I invited Mira to respond to Cha’s appearance in The Kitchen’s archive.

During a months-long conversation amongst Mira, Cha, and I, Mira created Tesseract (test), a portion of which is shared here publicly for the first time. Channeling Cha, Mira posthumously recreates the final scene of Cha’s last work-in-progress, White Dust from Mongolia (1980–). Like in many of Mira’s works, the sound and image are not manipulated or edited. Rather, we are witness to an arrival.

—Kathy Cho, 2020–2021 Curatorial Fellow

I am gifted two pairs of gloves. Because I live in Los Angeles, these feel like objects, props.

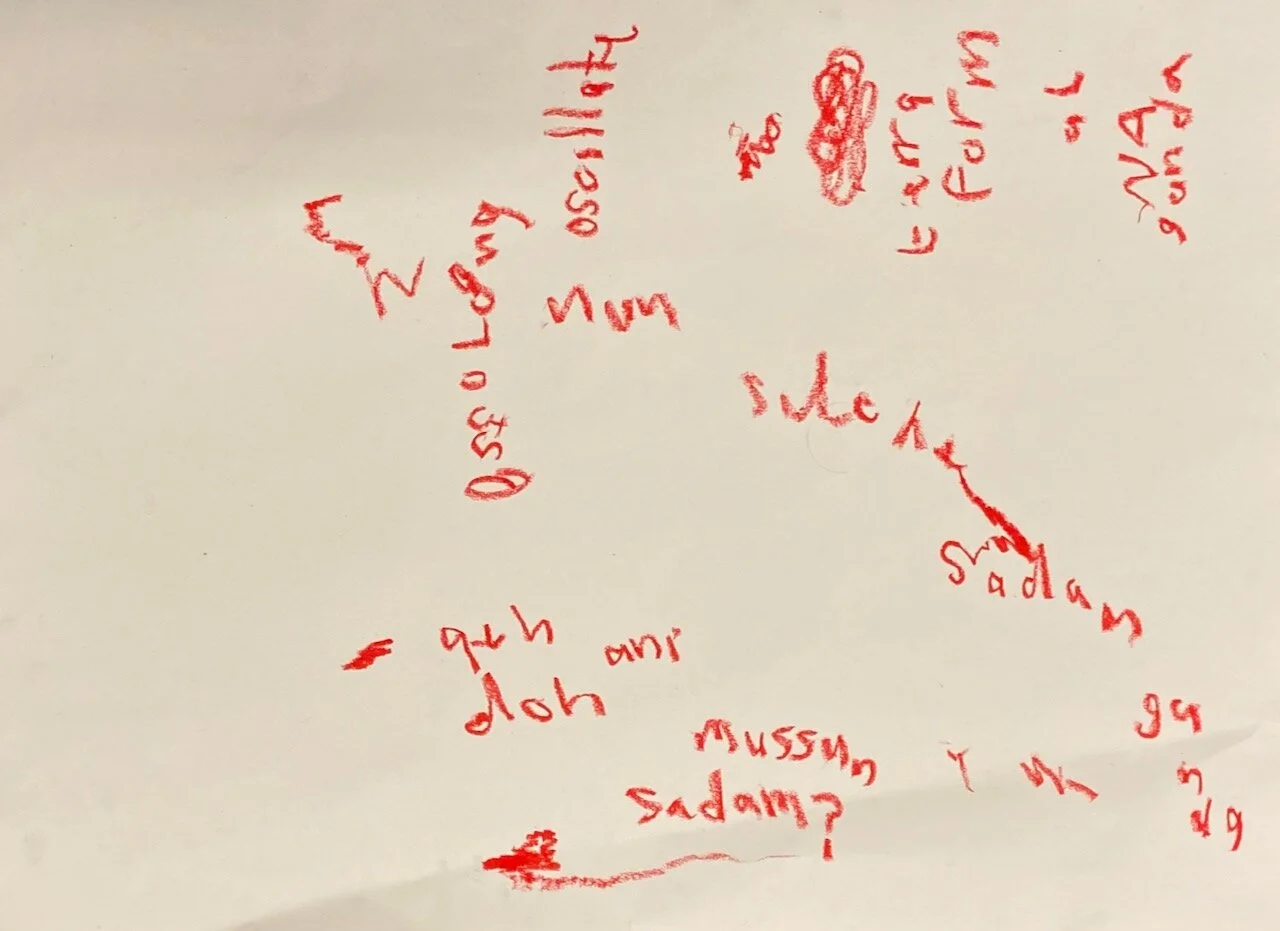

Today is my birthday and K-Sue teaches me the characters for the shaman ritual of riding the knives. I ask in my automatic writing—eyes closed, tongue prone, other handed:

Q: How do I ride?

A: NA NUN DULCHE SADAM GANDA

(My mother calls during and she translates the words: I am the second person going)

A candle burning on the altar explodes its glass when she speaks and I walk right into a fluorescent bulb. Everything pierced, sharp dust.

I return to Cathy Park Hong’s chapter in Minor Feelings on Theresa Hak Kyung Cha. A series of dreams, numbers, leads Cha’s brother to the site of her rape and murder. He finds her gloves: They looked alive…They were her final art piece.

You invite me to reflect on Cha a few days ago. Within a stack of feminist zines made by Asian teenagers in the ’90s, I see a photocopy of her electric utterance, shattered sentences. I’m working on something else, but I keep returning to Cha. I have been for decades. Her words cut the world I walked off. In Cha’s archives I notice a contact sheet full of hands. The photos are connected to her final unfinished film and book, White Dust From Mongolia. In the treatment she writes:

There exists a “Hole” in Time, a break in the linearity of Time and Space, and that empty space, the Absence, becomes the fixation, the marking that is the object of retrieval, a constant point of reference, identification, naming, the point of convergence for the narratives, the point of rupture, which gives, considers the multiplicity of narrative, multiplicity of chronology...

Cha proposes two narrators, one in the past who is trying to remember and a second in the present who is trying to remember. Throughout the piece the two points move towards each other eventually to one complete superimposition:

It is Character #2 who returns, gives memory to Character #1. #2 is the retriever (the activator) of the memory of the narrative by the process of recounting the Recit…

#2 is one who searches #1.

My exhibition The Book of Fixed Stars: Contrapunctual is postponed in March 2020. It’s still simmering. The Contrapunctual in the title comes from my automatic writing, like contrapuntal—a song with two different melodies playing simultaneously. I think of the word like a quantum superposition, the extra letters surface the puncture, punctum, in entanglement. Cha’s description feels so familiar to my project. I consider filming the final scene of White Dust From Mongolia where Character #2 walks into a projection of train tracks.

***

Q: What will happen if I record Cha’s piece?

A: TESSERACT

(a four dimensional square {4}x{4}, popularly used in science fiction to describe a portal to another world)

***

Brooke Intrachat is the other half Asian girl from my hometown. In 2019 I run into her while working on The Book of Fixed Stars. She is in Feng Shui school, so I ask her to make a reading of the gallery. A Feng Shui reading produces an I Ching hexagram. For the postponed show, the hexagram is 44: Coming to meet. One punctured yin line beneath five solid yang lines. The Wilhelm/Baynes translation of The Book of Changes interprets: The woman is strong. Do not marry. I interpret: I may destroy you. Sensing for what is next in the work, I follow 44 as it weaves in and out of these months.

There are 44 days between Cha’s death and my birth. A soul travels 49 days through the bardo. Maybe we met there? I look up shot 44 of White Dust From Mongolia. It is the same train tracks from the final scene, except Character #1 is inside the image waiting.

***

Q: How do the two selves meet?

A: SAMSARA

(cycle of life and death, rebirth)

SULLIGANG

(Korean moon dance ritual. I decide to film a test tomorrow, the full moon.)

***

I pour water for the ancestors and Cha. I ask for her permission and their protection.

Months ago my ancestors show me a tube, one in their hand and another like a channel of air. Then I learn of a Korean cosmology where the first vibrations of the world emanate from flutes of air. So I tape a latex tube to a small microphone. It is sensitive to the touch but tonight it won’t pick up my voice even with the amp turned high. I leave it on and begin recording the performance. I use my infrared camera which has been producing a glitch ever since I took it to Korea in 2018 to research my family’s shaman lineage. It repeats scenes from the past over the present, collapsing space, time. I project Cha’s train tracks, put on my gloves, and read out the automatic writing that led me here. An hour later I adjust the volume on the tube and suddenly so many sounds come out. New voices constantly, clipped, broken. Sometimes a whole phrase of a song, bells. It’s like a radio, but I have no radio.

Later, on another full moon, the sonic transmission returns. This time the voices speak at length in Korean: it is 1540 AM Korea Radio. Moving the tube, singing into it, creates resonance. Their voices rise with mine.

—Na Mira

Images and video: 1) Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, plan for Passages Paysages (detail), 1978. Handwritten text in pencil and ink on graph paper, 48 x 11 ¾ in. University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive; gift of the Theresa Hak Kyung Cha Memorial Foundation. 2) Left and right: Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, installation documentation from Passages Paysages, 1978. Black-and-white photographs; 10 x 8 in. each. University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive; gift of the Theresa Hak Kyung Cha Memorial Foundation. 3) Na Mira, sample of automatic writing, 2020. Courtesy of Park View / Paul Soto and the artist. 4) Na Mira, still fromTesseract (test), 2020. Infrared HD video, 5 minutes and 5 seconds. Courtesy of Park View / Paul Soto and the artist.