Lorraine O’Grady and Simone Leigh

By Alexis Jacquet, Fall 2021/Winter 2022 Curatorial Intern and Angelique Rosales Salgado, Curatorial Assistant

“From the Archives” is a series that spotlights The Kitchen’s history. As a complement to our Archive Website, these posts offer focused reflections on the artists, exhibitions, events, and institutional practices that have defined and shaped The Kitchen since its founding in 1971.

Lorraine O’Grady is a concept-based artist who works across text, photo-installation, video and performance, and whose contributions to art history and intersectional feminism have been paramount. We are proud to honor O’Grady as one of two honorees at the 2022 Kitchen Gala Benefit. On this occasion, we celebrate her sweeping legacy in community with The Kitchen’s history and in conversation with Simone Leigh, and artist working in sculpture, installation, video, and social practice, whose first institutional solo show was at The Kitchen in 2012.

“BLACK ART MUST TAKE MORE RISKS! Black art must take more risks!” In 1980, the artist Lorraine O’Grady interrupted the opening-night benefit of Just Above Midtown—a gallery founded by Linda Goode Bryant in 1974 that championed primarily Black artists and artists of color from New York City and Los Angeles. O’Grady made a scene as her performance persona Mlle Bourgeoise Noire (Miss Black Middle Class), a French-Guianese pageant winner dressed in a handmade ball gown made of 180 pairs of white gloves. Announcing her entrance with the exclamation above, Mlle Bourgeoise Noire handed out chrysanthemums from a heavy bouquet to a room full of surprised art patrons, artists and collaborators. Once the flowers were gone, she was left with what she called the “whip-that-made-plantations-move,” and proceeded to take off her cape and whip herself for five minutes while shouting poems protesting the segregated art world at that time. [1] This radical debut as O’Grady’s entrance into the art world has come to be known as one of her most celebrated and widely cited performances.

HERE AT THE KITCHEN, we are overjoyed to celebrate Lorraine O’Grady as one of our 2022 Gala Honorees for her revolutionary contributions and continued investment in experimental creativity. Through performance, video, collage, public art, and criticism, she focuses on the cultural constructions of identities, respectability politics, and her own personal history. For more than four decades, her practice has challenged cultural conventions and made space for multiple feminisms, holding a vital part of our shared New York downtown community. The Kitchen, since its founding in 1971 by artists Steina and Woody Vasulka, has fostered and evolved groundbreaking models for artists across its many chapters. Since the performance Mlle Bourgeoise Noire, O’Grady’s work has continued to bring multidisciplinary aesthetic issues to life—with a liveness and critical orientation—that resonate with artists who have presented at The Kitchen, including Jamal Cyrus, Bill T. Jones, Greg Tate, George Lewis and Simone Leigh.

AS A CONCEPTUAL ARTIST AND CULTURAL CRITIC, O’Grady demonstrates an intention and poetic commitment to process rather than resolution. She is an advocate of hybridity and presents alternatives to the hierarchical: creating images, ideas, and situations in her artwork, writing, and teaching that “allow binaries to be seen as reciprocal, or Both/And.” [2] O’Grady created the persona Mlle Bourgeoise Noire (MBN) in response to the exclusion of Black artists from a mainstream art world. MBN serves as a political character that represents elements of O’Grady’s identity—at an intersection of poetry and autobiography—as a middle-class woman of European and Jamaican descent. Material and sartorial interventions of the work—for example, the white gloves she wore— are symbolic of the internalized oppression of Black women to conform to the set of gendered beliefs established by respectability politics. The whip as an additional prop exemplifies the external oppression from art spaces, both in institutions’ often singular interpretation of Black artists, and in their direct exclusion of these artists’ work. The segregation of the art world in the 1980s prevented Black artists from gaining mainstream attention. O’Grady recalls that select Black artists in the 1980s who were receiving “mainstream” attention were tentative in voicing any frustrations, and this led them to shy away from explicit displays of resistance. [3] MBN was always an “equal-opportunity critic, or castigator,” O’Grady mentions. [4] She had no interest in presenting “safe, polished work”—her focus lay perhaps less on how Black artists fit into an already existing avant-garde, but in embracing a logic of doubleness to show how Black artists and artists of color shift our understandings of the origins of a total avant-garde.

RISKS ALSO RESIST. O’Grady’s personified critique of the art world enabled her to broadcast her Blackness, womanhood, and economic status as intersectional complexities which she emphasized in exhibition spaces. Her writing continues this work of choreographing new ways of seeing and feeling bodies across space too—the Black female body, the self (personified, framed, adorned, monumentalized) and the spirit of a body in its presence or absence. In her essay “Olympia's Maid” (1992), she writes: “the black female’s body needs less to be rescued from the masculine ‘gaze’ than to be sprung from the historic script surrounding her with significance.” [5] Her research as a critic sets an innovative precedent for how performance confronts societal conditions through implicit and explicit messages. In historian Uri McMillian’s words, O’Grady’s Mlle Bourgeoise Noire performance defines a sort of starting point for “the rebuke to the perceived incommensurability of a Black avant-garde.” [6]

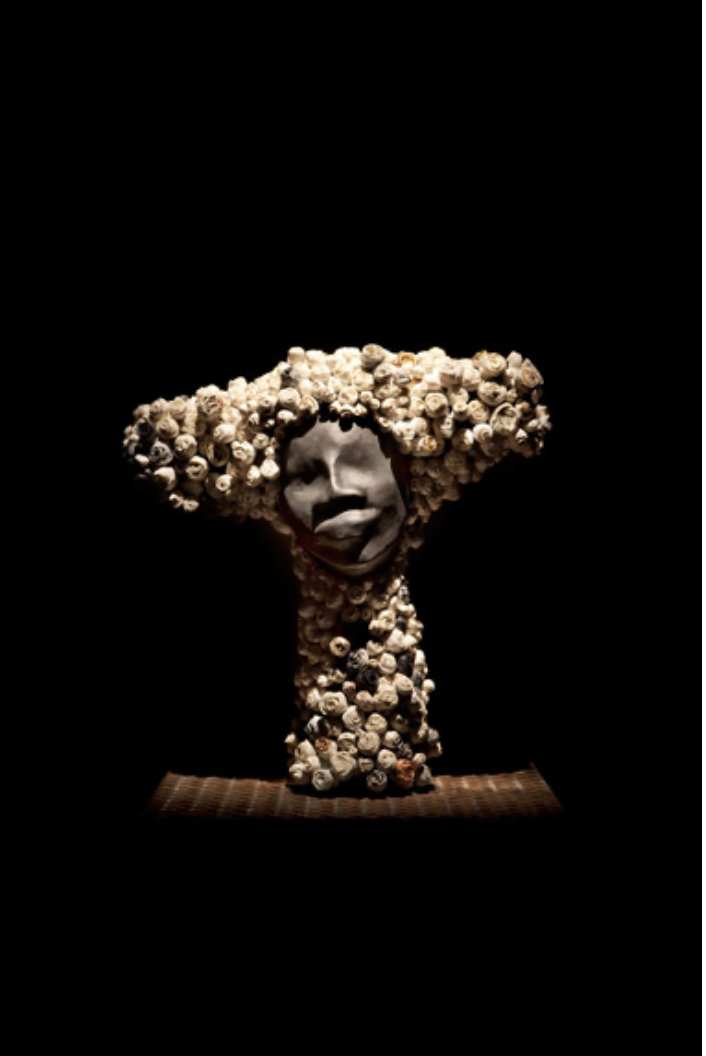

SIMONE LEIGH’S FIRST INSTITUTIONAL SOLO EXHIBITION, You Don’t Know Where Her Mouth Has Been, was organized by Rashida Bumbray at The Kitchen in 2012. Leigh engages in object-based explorations of Black female subjectivity through sculpture, video, and site-specific installation informed by her interests in African art, ethnographic research, feminism, and performance. Her practice reimagines perceptions of Black “women’s work” throughout history, in artworks that incorporate both historic ceramic techniques and digital media. [7] O’Grady’s modernist and subversive lines of thinking has been informative for subsequent generations of artists like Leigh—who herself has described O’Grady as a “foremother” for her work. In her solo presentation at The Kitchen, Leigh debuted new bodies of work: three sculptural chandelier installations, a tripartite vase flanked on either side by rows of giant odiferous tobacco leaves, a bust sculpture, and two video installations. Illuminated by spotlights throughout The Kitchen’s gallery (painted black for the installation), Leigh scales drama to create assemblages that are at once futurist and ancestral, where imagined futures meet connected pasts. Delving into histories yet to be explored, Leigh’s practice can be understood as carrying forward O’Grady’s unwavering sensibility of persistence.

BETWEEN O’GRADY AND LEIGH, a cross-generational dialogue of aesthetic resistance can be connected between works on view in Leigh’s multidisciplinary exhibition at The Kitchen, like Herero Dress 1904 (2011), and O’Grady’s 1980 performance Mlle Bourgeoise Noire. Leigh’s sculpture, a portrait in graphite and epoxy of a Black woman with hair made of white porcelain roses, manifests the “[springing] from the historic script” O’Grady speaks of in her writing. Similar to Mlle Bourgeoise Noire, the Herero people that Leigh is casting, figuratively, within her works call upon notions of respectability related to colonization. Herero Dress 1904 interrogates the cultural construction of identity by signaling the moment of historical significance referenced in the title: the 1904 rebellion of Namibia’s Herero people against the Germans, after which the surviving women adapted Victorian-style dresses, called ohorokova, as a symbol of resilience. The Namibia’s Herero community focused on the cultural significance embedded within a European style of dress and reinterpreted its purpose to illustrate their own personal history bound up within it. Whereas O’Grady utilizes her body in performance to express resistance, Leigh’s material explores Black women’s subjectivity across diasporas. Both artists confront this historic script, perhaps in an effort to “de-haunt” it and establish agency: as O’Grady has stated, “subjectivity for me will always be a social and not merely a spiritual request.” [8] They both spring a vernacular Caribbean image into a variation of new media, emphasizing how living histories form and deform material.

ON THE OCCASION OF LEIGH’S LOOPHOLE OF RETREAT exhibition and convening at the Guggenheim in 2019, O’Grady—who was invited to present at the conference—introduced the notion of “self-blinding,” visible in many of Leigh’s sculptures that lack eyes, including Herero Dress 1904 . That intervention in Leigh’s work, O’Grady calls a “radical act of self-preservation that shuts out the exterior long enough to be able to pay deep attention to the interior.” [9] In response, she asks: “How brave and how honest will we be when we begin to look inside. What is one willing to see?” [10] The intersection of both artists' practices here makes porous the participatory threshold of risk taking cited by O’Grady in 1980 and embodied now by artists who join the conversation. In her exclamation of the desire to risk-take, whether silent or amplified, there is a collective invitation. An inward-looking history is made external by the interwoven experimental exchange unfolding throughout The Kitchen—one among a nexus of spaces that endure to shape alternatives.

Images: 1) Lorraine O’Grady, Untitled (Mlle Bourgeoise Noire leaves the safety of home), 1980-83/2009. Courtesy Alexander Gray Associates, New York. © 2022 Lorraine O’Grady / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. 2) Lorraine O’Grady, Untitled (Mlle Bourgeoise Beats Herself with the Whip-That-Made-Plantations-Move), 1980-83/2009. Courtesy Alexander Gray Associates, New York. © 2022 Lorraine O’Grady / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. 3) Simone Leigh, You Don't Know Where Her Mouth Has Been, 2012. Curated by Rashida Bumbray. Installation view at The Kitchen, January 18–March 11, 2012. Photo by David Allison. 4) Simone Leigh, Herero Dress 1904, 2011. Installation view at The Kitchen, January 18–March 11, 2012. Photo by David Allison.

Footnotes:

[1] “Under the Cover: Lorraine O’Grady," Artforum, March 10, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zDhV2tI9img&list=TLPQMTkwMTIwMjKN5SmCEiZq5Q&index=3, 15:12.

[2] Malik Gaines, “We Must Try to Be Analytic with Our Recuperation” in Lorraine O’Grady: Both/And , ed. Catherine Morris and Aruna D’Souza (Brooklyn: Dancing Foxes Press, 2020), 80.

[3] Aruna D'Souza, Lecture and Discussion - Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And , UH School Art, September 25, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=51OKf7TRXEo&t=1341s, 22:22.

[4] Lorraine O’Grady, “Statement for Moira Roth re Art is…”, Unpublished email exchange, 2007, http://lorraineogrady.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Lorraine-OGrady_Statement-for-Moira-Roth-re-Art-Is_Unpublished.pdf.

[5] Lorraine O’Grady, “Olympia's Maid: Reclaiming Black Female Subjectivity,” 1992–1994, https://lorraineogrady.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Lorraine-OGrady_Olympias-Maid-Reclaiming-Black-Female-Subjectivity1.pdf.

[6] Uri McMillan, Embodied Avatars: Genealogies of Black Feminist Art and Performance (New York: NYU Press, 2015), 20.

[7] Documentation of Simone Leigh's creative process in Women’s Work, directed by Ja’Tovia Gary (2012).

[8] O’Grady, “Olympia's Maid."

[9] Lorraine O’Grady, “Loophole of Retreat: A Conference Part 3 of 3,“ Guggenheim Museum, May 3, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WeRQVFCY8y4 , 1:08:42.

[10] Ibid.